As a child immigrant, I was told both explicitly and implicitly that I needed to disown my Korean-ness. The goal was to become “Americanized,” and not be seen as “foreign.” As a Korean-American, I have a very complicated relationship with being white adjacent and the model minority myth.

A couple of months ago, I came across this line in a poem by Amanda Gorman:

“Something in us repents every time a new friend doesn’t tell us their given name, preempting our tongue to lay a violence toward that too.”

That line opened a locked room inside me that housed so much grief and sadness which I have suppressed in an effort to survive.

One way that I am healing from racialized trauma is by re-remembering the essential parts that make me who I am and re-remembering my ancestors.

When I started my journey with Resmaa Menakem and his seminal work, My Grandmother’s Hands, Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies, I felt overwhelmed by the depth of grief and sadness. He didn’t offer any “tools” or quick fixes. He told me to be with the experience but also to remember to back away from it and give it space. As he says, “Nibble, don’t gorge.”

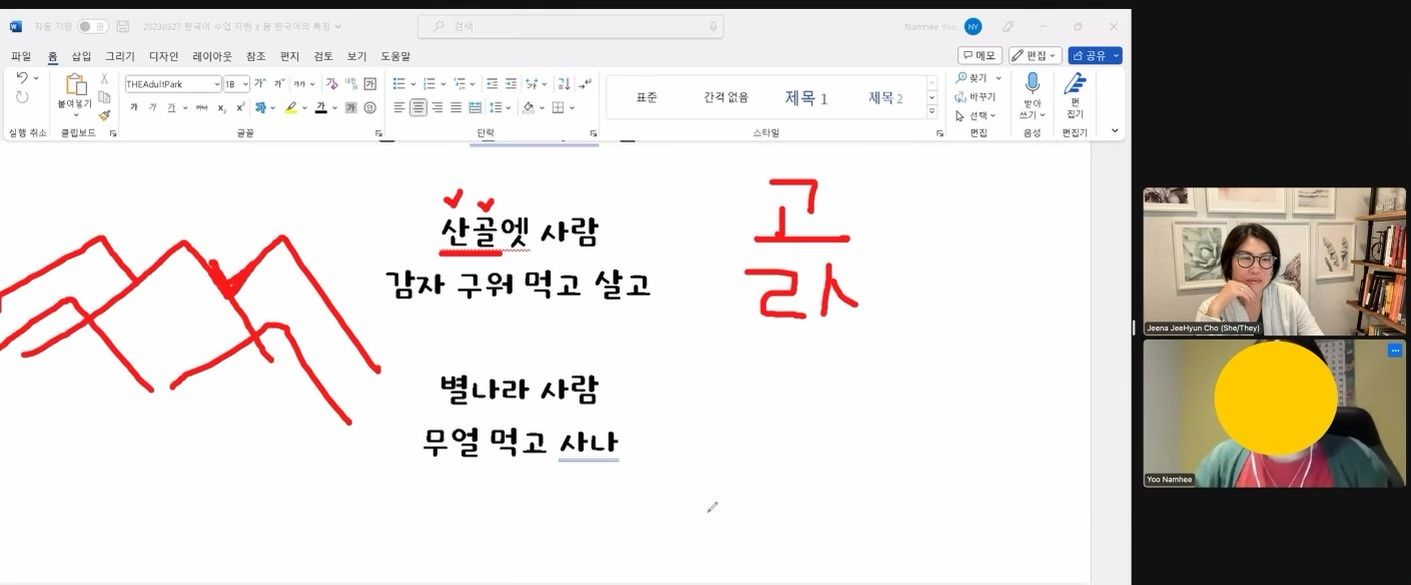

Several months ago, I started taking Korean lessons online. It’s often a very tender experience, feeling my mouth form the words and hearing Korean come out of it. It feels like a reclaiming of my birthright and a reintroduction to a part of myself that I had forgotten, yet, not forever lost to me.

I am falling so deeply in love with my mother tongue and slowly allowing the emerging of myself.